Introduction

Une compilation de références sur l’impact environnemental de la lumière selon son contenu spectral.

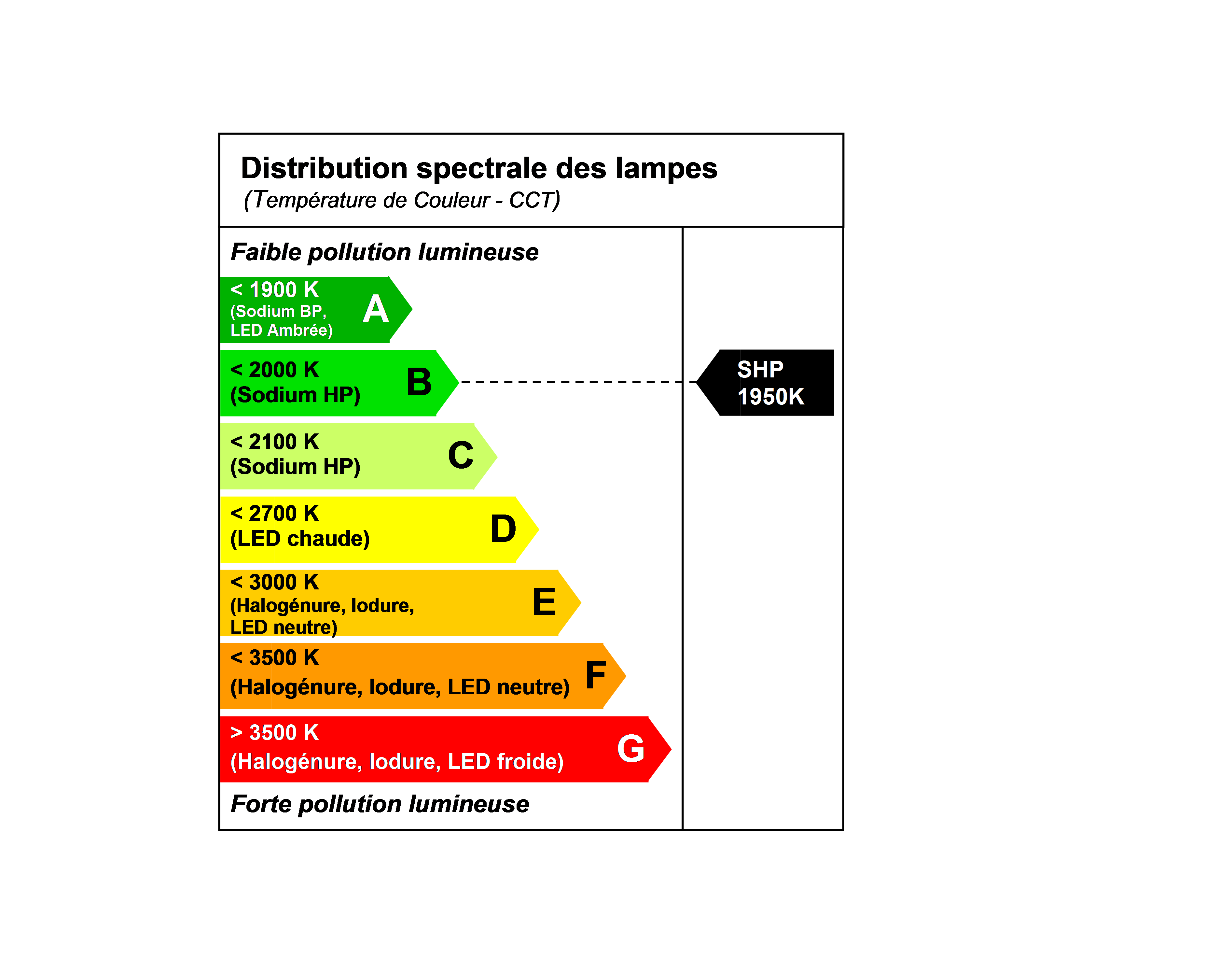

La question du contenu spectral est d’importance dans la mesure où les lampes Sodium Haute Pression, à lumière jaune (température de couleur < 2000 kelvins), sont souvent écartées maintenant, au profit de lampes à lumière blanche (température de couleur > 3000 kelvins) (iodures métalliques, LEDs). En particulier dans les zones commerciales, sur les trottoirs, et de plus en plus pour la voirie de centres-villes. L’intérêt de la lumière blanche étant le plus grand respect des couleurs.

On distingue deux impacts de la lumière sur l’environnement : l’un sur le paysage (ciel étoilé,…), avec les halos au-dessus des territoires éclairés, et l’autre sur le vivant.

La lumière blanche multiplie ces deux impacts par rapport à la lumière jaune.

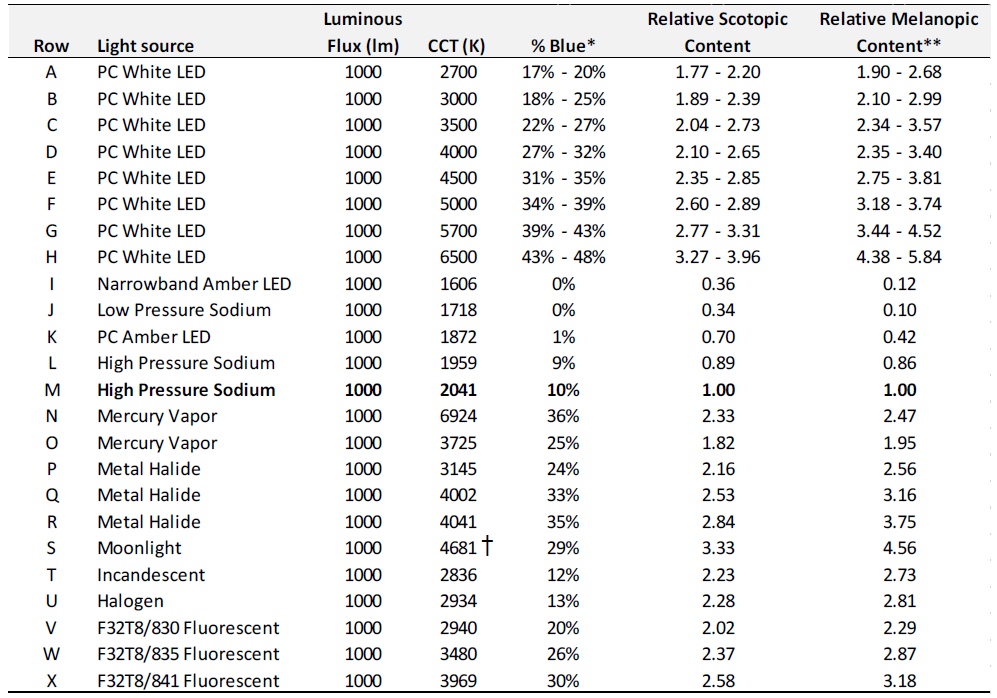

Contenu spectral des sources

Le document Street_lighting_and_Blue_Light_FAQs.pdf propose une compilation du contenu spectral de différentes sources.

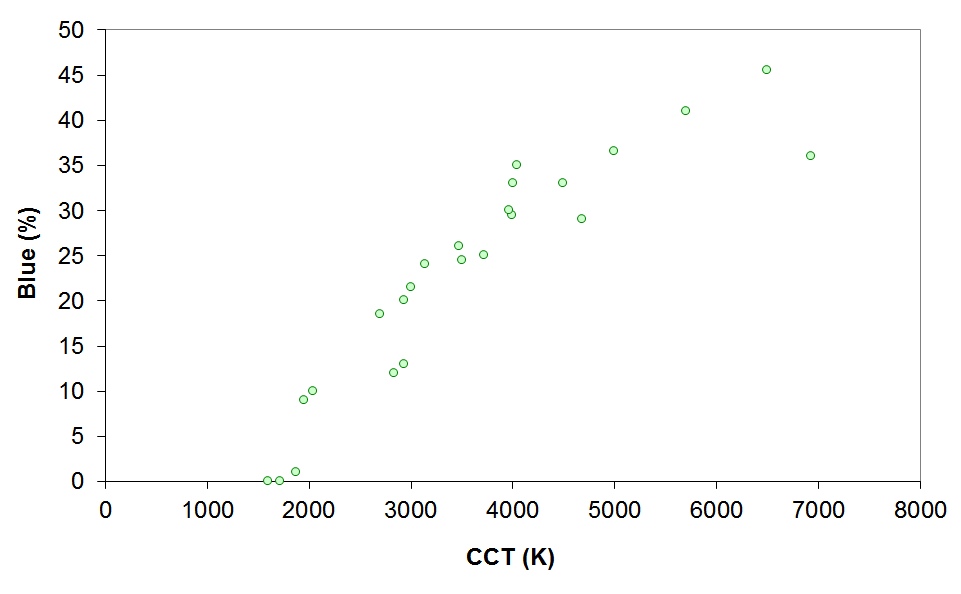

Le graphe suivant illustre la corrélation obtenue entre le contenu en bleu et la Correlated Color Temperature (CCT) présentés dans le tableau ci-dessus.

Impact paysager

La lumière est diffusée dans l’atmosphère. Pour cette raison on voit la trace de la lumière d’un projecteur dans le ciel, un halo au-dessus des villes,…

La lumière est diffusée parce qu’elle éclaire des gouttelettes d’eau, des poussières en suspension (diffusion de Mie), et les molécules d’air elles-mêmes (diffusion de Rayleigh).

La diffusion de Mie est indépendante de la longueur d’onde, mais la diffusion de Rayleigh en dépend à la puissance 4.

Renforcer le contenu spectral des lampes vers le bleu amplifie la diffusion de Rayleigh et donc la taille et l’intensité des halos.

Différentes publications rendent compte de ce phénomène

- PhysicsTodayDecember2009. Présente l’évolution de la pollution lumineuse. Le contenu spectral est abordé.

- An Investigation of LED Street Lighting’s Impact on Sky Glow (2017). Une étude du département américain de l’énergie, ciblée sur les LEDs.

- Diminuer halos lumineux proteger ciel & Environnement – A Le Gue N Bessolaz 2009. Cet article expose la manière dont le contenu spectral détermine l’intensité des halos.

- Baddiley&Webster. Même thématique, avec un paragraphe consacré à l’importance relative des diffusions de Mie et de Rayleigh.

- Baddiley_Sky_Luminance. Même propos. Influence de la longueur d’onde p. 35.1

- Skyglow modelling CJB. Même propos. Influence de la longueur d’onde p. 59-61.

- GPU Gems – Accurate Atmospheric Scattering. Pour l’anecdote, les créateurs d’images virtuelles s’intéressent aussi à la modélisation de la diffusion de la lumière, Mie et Rayleigh…

Impact sur le vivant

Soirée d’été en Ile-de-France :

L’impact de la lumière est renforcé avec le contenu spectral vers le bleu. Des articles rendent compte de l’impact sur les insectes, mais aussi sur le cycle circadien de l’homme.

Des températures de couleurs inférieures à 3000 kelvins seront préconisées pour contenir l’impact environnemental.

Différents articles présentent l’impact de la lumière en fonction du contenu spectral :

- Une bibliographie importante est disponible. Quelques exemples sont proposés ci-après.

- Brainard all 2001. Concerne la biologie humaine, montre que le bleu est le plus actif sur le cycle circadien ou la régulation de la sécrétion de la mélatonine.

- Brainard et Glickman. Traduction d’un article sur l’action de la lumière et de son contenu spectral sur le cycle circadien. Brainard et d’autres, publient régulièrement sur l’influence de la lumière sur le métabolisme :

- Brainard, G. C., G. Glickman, B. Sanford, J. Greeson, J. Hanifin, B. Byrne, E. Gerner and M. Rollag (2000) Human circadian photoreception: action spectrum for melatonin suppression. Abstr. 13th Internat. Congr. Photobiol., 697

- Gooley, J., Brainard, G., Rajaratnam, S., Kronauer, R., Czeisler, C. and Lockley, S. (2007) Spectral sensitivity of the human circadian timing system. PO073, ‘worldsleep07’, 5th congress of the World Federation of Sleep Research and Sleep Medicine Societies, 2-6 September 2007, Cairns, Australia. Abstract in Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 5, A22 (2007).

- Thapan K, Arendt J, Skene DJ, 2001, An action spectrum for melatonin suppression: evidence for a novel non-rod, non-cone photoreceptor system in humans. J.Physiol, 535, 261-267.

- Takahashi, J. S., P. J. DeCoursey, L. Bauman, and M. Menaker (1984) Spectral sensitivity of a novel photoreceptive system mediating entrainment of mammalian circadian rhythms. Nature 308, l86-l88.

- Marc Théry, Conséquences écologiques de l’éclairage nocturne sur la faune. Éclairages extérieurs – Les nuisances dues à la lumière, guide 2006. Association Française de l’Éclairage.

- IDA. Le positionnement de l’International Dark-Sky Association, alerte sur l’impact de la lumière blanche sur le cycle circadien.

- Green_light_to_birds. La réduction du rouge dans le spectre des lampes d’une plate-forme pétrolière pour minimiser l’attraction des migrateurs. En effet, les oiseaux migrateurs, eux, paraissent sensibles au rouge.

- Eisenbeis. Un article consacré à l’attractivité des lampes sur les insectes selon leur contenu spectral. Les lampes sodium jaunes sont les moins attractives. Toutefois leur impact reste considérable.

Résumé : Street lamps which illuminate public areas and places at night are of different types, emitting different spectra. All of them (e.g. white mercury (HME), orange sodium (HSE) or sodium-xenon vapour lamps (HSXT)) attract insects. During summer nights, myriads of insects fly restlessly around the lamps, which therefore have a marked impact on insect biology. There is some evidence that lamps differ with respect to their insect attraction. Sodium lamps, for instance, attract insects less strongly than white mercury lamps. We tested the attraction of three lamp types and, in addition, an ultraviolet absorber foil and some controls (lights without illumination). All installations were carried out by the electric utility of Rheinhessen/Germany (EWR) at three sites in a rural area. To trap insects, we used 19 air-eclector traps which had been positioned within the light cones of the street lights. We caught a total of 44,210 insects (including some arachnids), distributed among 12 orders. Altogether the data set comprised 536 night trapping records. The results show that the number of insects captured at the three sites and the attraction per eclector per day depends significantly on both the type of lamp and the site. By using sodium vapor street lamps (HSE), the number of insects caught was reduced signficantly by more than 50%, and in the case of Lepidoptera by about 75%. We therefore recommend the use of sodium high pressure vapour lamps to improve the conservation of insect fauna. The results further show that there is a large potential to reduce costs for municipalities by switching street illumination from mercury vapour (HME) to sodium vapour (HSE) lamps.

- Aubineau. Une étude importante sur l’attractivité de différentes sources lumineuses sur les insectes.

- Ashfaq. Efficacité de la couleur des sources lumineuses pour le piégeage des insectes, comme alternative aux pesticides. La couleur bleue est la plus efficace.

- Pate-Curtis. Même type d’étude et de résultat.

- Potter2002. Idem.

- Walker-Galbreath. Idem. L’association de différentes sources, enrichissant le spectre, conduit à la plus grande attractivité.

- James-Smith. Même type d’étude. L’UV (lumière noire) domine. Bleu, blanc, et vert sont comparables et sont beaucoup plus attractifs que le jaune.

- Alberto-Kirschbaum. Incidence de la température de couleur sur l’attractivité des insectes.

- Ramamurthy. Efficacité de différentes sources lumineuses pour le piégeage des insectes, comme alternative aux pesticides. Le spectre du mercure est le plus efficace.

- Eisenbeis and Hanel. Une synthèse de l’impact de la lumière sur les insectes, avec l’aspect spectre des lampes. Le mercure est beaucoup plus attractif que le sodium.

- Scheibe_thèse, Scheibe_2, Scheibe_3. Les travaux de Mark Andreas Scheibe sur l’attractivité de la lumière sur les insectes aquatiques. Pas de conclusion simple quant aux effets du contenu spectral.

Quelques référence supplémentaires qui abordent le contenu spectral de la lumière :

- Buchanan, B. W. 1993. Effects of enhanced lighting on the behaviour of nocturnal frogs. Animal Behaviour 45(5): 893 to 899.

Résumé : Biologists studying anuran amphibians usually assume that artificial, visible light does not affect the behaviour of nocturnal frogs. This assumption was tested in a laboratory experiment. The foraging behaviour of grey treefrogs, Hyla chrysoscelis, was compared under four lighting conditions: ambient light (equivalent to bright moonlight, 0.003 lx), red-filtered light (4.1 lx), low-intensity ‘white’ light (3.8 lx), and high-intensity ‘white’ light (12.0 lx). The treatments were chosen to correspond to standard methods of field observation of frog behaviour. The foraging behaviour of frogs in the four treatments was observed using infra-red light that was invisible to the frogs. The ability of the frogs to detect, and subsequently consume prey was significantly reduced under all of the enhanced light treatments relative to the ambient light treatment. Thus, the use of artificial light, within the visible spectrum of the frog’s eyes, can influence the outcome of nocturnal behavioural observations. These results lead to the recommendation that anuran biologists use infra-red or light amplification devices when changes in frogs’ visual capabilities may influence the conclusions drawn from a study.

- FUKUDA, N. et al. (2002).- Effects of light quality, intensity and duration from different artificial light sources on the growth of petunia (petunia x hybrida vilm.). Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural. Science, 71(4) : 509–516.

- GAL G., LOEW E.R., RUDSTAM L.G. & MOHAMMADIAN A.M. (1999).- Light and diel vertical migration spectral sensivity and light avoidance by Mysis relicta. Can. J. Fish Aquat. Sci 56 : 311-322.

- GAUTIER, H. et al. (1998).- Comparison of horizontal spread of white clover (Trifolium repens l.) grown under two artificial light sources differing in their content of blue light. Annals of Botany, 82(1) : 41–48.

- Govardovkii, V. L. and L. V. Zueva, 1974. Spectral sensitivity of the frog eye in the ultraviolet and the visible region. Vision Research 14:1317-1321.

- Hailman, J. P. and R. G. Jaeger. 1974. Phototactic responses to spectrally dominant stimuli and use of colour vision by adult anuran amphibians: a comparative survey. Animal Behaviour 22:757-795.

- Hartman, J. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1981. Interactions of light intensity, spectral dominance and adaptational state in controlling anuran phototaxis. Zietschrift für Tierpsychologie 56:289-296.

- Jaeger, R. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1976. Ontogenetic shift of spectral phototactic preferences in anuran tadpoles. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 90:930-945.

- Jaeger, R. G. and J. P. Hailman. 1976. Phototaxis in anurans: relation between intensity and spectral preferences. Copeia 1976:92-98.

- Kicliter, E. and E. J. Goytia. 1995. A comparison of spectral response functions of positive and negative phototaxis in two anuran amphibians, Rana pipiens and Leptodactylus pentadactylus. Neuroscience Letters 185:144-146.

- Kolligs, D. (2000). « Ecological effects of artificial light sources on nocturnally active insects, in particular on butterflies (Lepidoptera). » Faunistisch-Oekologische Mitteilungen Supplement 28:1-136.

Résumé : It is a well known phenomena that night-active insects are attracted by artificial light sources. With a growing urban environment and a high number of street lamps and other light emitting sources, the response of night active insects to artificial light becomes of in-creasing importance for nature protection. This study focuses on the behavioural response of different insect orders, families and species to the most frequently used exterior lighting and street lamps (mercury- and sodium-vapour lamps). These artificial sources of light distinctly increased in the last decades. In the city of Kiel (North-Germany) the number of streetlights was fifty times higher in 1998 than in 1949. The investigations were carried out at two sites in Schleswig-Holstein (North-Germany): in Albersdorf / Dithmarschen (western Schleswig-Holstein) and in Kiel on the university campus (eastern Schleswig-Holstein). In Albersdorf, the insects were attracted by a light emitting greenhouse (10,000 m2) and by two punctually radiating light sources (light traps with mercury and sodium-vapour lamps) and became comparative investigated in 1994 to 1995. Two different methods were used to record insects at the greenhouse. Butterflies (Lepidoptera) were sampled by hand. The remaining insects were trapped in two 1.5 m2 large sample areas using a suction trap. Insects from each of the four sides of the green-house were sampled and trapped separately. The two light traps caught the insects automatically. On the campus of Kiel University insects were studied from 1994 to 1996. For this purpose four street lamps equipped with mercury-vapour lamps had traps attached to the socket. On one of the four street lamps the mercury-vapour lamp was exchanged by a sodium-vapour lamp with the same light intensity. In 1996 two additional street lamps were equipped with a different type of trap. 72,267 insects from 114 insect families and 96,725 insects from 138 families were redorded at Albersdorf and at Kiel, respectively. Butterflies (Lepidoptera), beetles (Coleoptera), caddies flies (Trichoptera) and sciarid flies (Sciaridae) were determined to the species level. An analysis of the catches gave the following resuits: Mosquitos (Nematocera) made up the majority of all captured insects (40 – 90 %). The other most conunon groups were butterflies (Lepidoptera), flies (Brachycera) and beetles (Coleoptera). In both study areas Hymenopterans (Hymenoptera), aphids (Aphidina), cicadas (Cicadina), true bugs (Heteroptera), neuropterans (Neuroptera), caddis flies (Trichoptera), psocids (Psocoptera) and mayflies (Ephemeroptera) made up less than 1 % of the total catch. Catches from adjacent street lamps (25 m apart) were distinctly different in their insect compositions. These differences seem to be caused by the surrounding habitats and the wind exposure of the lamps. Significant differences between the compositions of samples from different street lamps were oniy found between May and the end of August. In spring and autumn the sample 13 sizes were small and species compositions were not significantly different. In contrast to hand sampling not all insects that flew into street lamps were caught by the automatic light traps (e. g. only 30-40 % of the Lepidoptera were caught by the traps) No significant correlation was found between the size of a light source and the number of Lepidoptera attracted by it. Rather the intensity and the light spectrum seem to control butterfly abundance at a light source. The light spectrum of the sodium-vapour lamp attracted fewer species and individuals than the mercury-vapour lamp. Otherwise from some species, e.g. he swift mohs (Hepialidae) or the geometric moth Idaea dimidiata, more individuals were registrated at the sodium-vapour lamps. Only single individuals of endangered butterfly species were found at the different light sources, while 31 beetle species of the Red List of Schleswig-l-Iolstein were captured in the study area in Kiel.

- Korkosh, V. V. (1992). « Behavior of Atlantic saury and features of its response to light. » Voprosy Ikhtiologii 32(4):132-137.

Résumé : The behavior of Atlantic saury was studied in an artificial light environment. It is found that the response of the fish to light varies during the year and is determined by biological and ecological factors. The effectiveness of attraction of the fish to light depends on the power and spectral characteristics of light sources. A suggestion is made to use xenon bulbs DKST-20,000. It is established that attraction to light in Atlantic saury is based on the food procurement factor.

- OKAMOTO, K. et al. (1996).- Development of plant growth apparatus using blue and red led as artificiallight source. Acta horticulturae, 440 : 111–116.

- Reed, J. R., 1985, Seabird Vision: Spectral Sensitivity and Light Attraction Behavior, Ph. D. Thesis, Univ. Wisconsin (Madison), 200p.

- Reed, J. R., 1985, Seabird Vision: Spectral Sensitivity and Light Attraction Behavior,. Abstract in Int. B. Sci. Eng., 47(4), 1452.

Le cas des LEDs

Avec l’avènement des LEDs et leur spectre à forte composante bleue, l’impact de la lumière est reconsidéré.

Les références suivantes illustrent la spécificité de la lumière issue des sources LED.

- Memorandum – Light Pollution by Road Lighting (Hera Luce, 2017). Une synthèse des propriétés de la lumière selon la nature des sources, en termes de diffusion atmosphérique, comme de perception photopique, mésopique et scotopique.

- Human and Environmental Effects of Light Emitting Diode (LED) Community Lighting (Kraus, AMA 2016). Avis émis par l’American Medical Association, qui confirme celui de l’ANSES de 2010 (cf. point plus bas).

- Cet avis de l’AMA, ci-dessus, a donné lieu à une notice explicative sur le contenu spectral, Street Lighting and Blue Light FAQ, de la part du European Environmental Bureau (EEB), dans laquelle les propriétés spécifiques des différentes sources de lumière sont passées en revue, particulièrement la proportion de bleu émises par les différentes sources.

- LEDs-ANSES (2010). Dans un communiqué du 19 octobre 2010 (saisine 2008-SA-0408) sur les « Effets sanitaires des systèmes d’éclairage utilisant des diodes électroluminescentes (LED) », l’Agence Nationale de SEcurite Sanitaire (ANSES) souligne le déséquilibre spectral des LEDS vers le bleu, et la très forte luminance des sources (éblouissement). L’ANSES émet des recommandations visant à protéger la population par une révision de la norme NF EN 62471 relative à la sécurité photobiologique des lampes, concernant certaines LEDs bleu roi ou blanc froid (contenu bleu et Ultra-Violet significatif), encore renforcé avec le vieillissement de la LED.

- LUX n°234. Un dossier de l’Association Française de l’Eclairage. Le potentiel biologique de la lumière chez les hommes : importance pour notre santé et notre comportement. La lumière que reçoit l’œil active un chemin du système nerveux qui régule la physiologie du système circadien et neuroendocrinien. Ce chemin est séparé de manière prédominante de celui de la vision et des différents réflexes visuels. Une rupture des systèmes circadiens et neuroendocriniens, qui peut résulter de changements saisonniers, journaliers ou rapides à l’exposition habituelle à la lumière peut contribuer à générer divers troubles, cliniques ou non. Il est désormais bien établi que l’exposition à une lumière judicieusement dosée peut être utile dans le traitement et la prévention de ces troubles. A long terme, ces découvertes devraient aboutir au développement de solutions d’éclairage optimales pour la vision, la santé physiologique et le bien-être de tous.